Royal National Theater Studio Workshop Production.

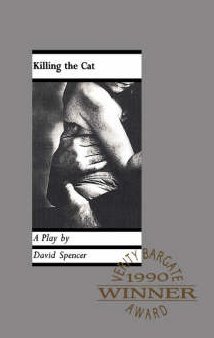

Killing the cat

September 13th, 1990

Presse und Rezension:

Aufführungen:

- Royal Court Upstairs for Soho Theater Company

Sprachen:

- Englisch

- Deutsch

The Independent: Killing the cat

September 13th, 1990

Date: 09/13/1990

Author: Georgina Brown

David Spencer’s Killing the Cat explores the repercussions for a working-class family

when the son writes a novel exposing his father’s sexual abuse of his daughter. It is

Spencer’s second winner of the Verity Bargate Award for new writers and an exceptional piece – dense, demanding and boldly conceived, and here given a searing production by Sue Dunderdale and a superb cast.

Danny (Sean Bean at his most transfixing) and his sister Sheilagh (played with raw

emotion by Sally Rogers) hate their father, Sam, for what he has done to Sheilagh; but they love him because he is their father. Spencer allows his characters and their

relationships to be infinitely complex, riddled with plausible ambiguities and

contradictory emotions, and as a result they are frighteningly real. It’s the

children’s inability (or perhaps determined refusal) to hate their father that

suspends our moral judgement of him. A scene in which Sam sits mindlessly watching a train set go round and round provides one of many details through which Spencer invites our sympathy for him – his childhood in an orphanage, the hatred Irish immigrants face, his wife’s coldness. Alan Devlin gives a superlatively horrible performance as Sam, proud, pugnacious and pissed, unquestioningly sentimental about his kids and himself and stone-deaf to criticism.

With almost cinematic fluency, the play slips backwards and forwards in time and place. The clever, gentle child (Dominic Kinnaird) who hero-worshipped his father is seen in sharp juxtaposition with the cynical adult he has become, a writer full of rage on behalf of his sister. The catharsis he experiences in writing about the abuse

(”I was born with too many feelings. If I didn’t find anywhere to put them, I’d

die of them”) is for Sheilagh a second invasion , which raises pertinent questions

about a writer’s right to feed on other people’s lives.

It is hard to pin down the narrative any more precisely than the play’s oblique title.

This might refer to a flashback scene in which a pet cat has been run over and Sam

puts it out of its misery, an act that always haunted Danny. Or it might refer to

the fact that Danny could wreak vengeance on his father by killing the cat Sam is

besotted with. But the validity of each individual’s version of reality and the

inevitably imperfect understanding of another’s point of view are exactly those

areas that Spencer is exploring. The imaginative power of his play lies in its

insistence that we pay attention.

Killing the cat

September 13th, 1990

Killing the Cat is a play about memory and writing. Moving between the 70s and the present day it shows Danny writing about his sister’s experience of sexual abuse by his father. As he invents a fiction of what he has been told has happened, what he remembers happening and what he imagines or dreams to have happened in the past Danny’s story threatens to blow the family apart, until the other members join ranks to keep the story a family secret.

Killing the Cat is a play about memory and writing. Moving between the 70s and the present day it shows Danny writing about his sister’s experience of sexual abuse by his father. As he invents a fiction of what he has been told has happened, what he remembers happening and what he imagines or dreams to have happened in the past Danny’s story threatens to blow the family apart, until the other members join ranks to keep the story a family secret.

Press and reviews:

On Stage:

- Royal Court Upstairs for Soho Theater Company

Languages:

- English

- German

DAILY MAIL: Killing the cat

September 9th, 1990

Date: 09/19/1990

Author: John Marriot

Focus on a family at war

Blessed by David Spencer’s lean script which ensures that anger bounces off

the walls of this tiny venue with full force, this impressive piece links family

break-up to social unrest, and provides meaty roles for an excellent cast.

Centering on the uneasy introspection of Danny (Sean Bean), who makes a trip

back to Yorkshire to grapple with his family background, “Killing the Cat” also

draws in a vivid portrait of a weak, blustering father (Henry Stamper) and

flashes back to a happy childhood which lasted until love was broken into tiny

pieces.

Sean Bean holds the centre well as Angry Young Danny, veering convincingly

from volcanic rage and biting cynicism, to weepy sensitivity and all-out

kindness. Henry Stamper provides a visceral treat as a father trapped by his

own insecurity.

Kate McLoughlin and Sally Rogers offer confident support as Danny’s two

sisters, while Valerie Lilley, as the mother, fixes your gaze with her descent

toward mental illness.

This harrowing scenario of alienation and lost love is thankfully punctured

by bouts of earthy humour. The acting is so electric the cast almost sits in

your lap.

the walls of this tiny venue with full force, this impressive piece links family

break-up to social unrest, and provides meaty roles for an excellent cast.

Centering on the uneasy introspection of Danny (Sean Bean), who makes a trip

back to Yorkshire to grapple with his family background, "Killing the Cat" also

draws in a vivid portrait of a weak, blustering father (Henry Stamper) and

flashes back to a happy childhood which lasted until love was broken into tiny

pieces.

Sean Bean holds the centre well as Angry Young Danny, veering convincingly

from volcanic rage and biting cynicism, to weepy sensitivity and all-out

kindness. Henry Stamper provides a visceral treat as a father trapped by his

own insecurity.

Kate McLoughlin and Sally Rogers offer confident support as Danny's two

sisters, while Valerie Lilley, as the mother, fixes your gaze with her descent

toward mental illness.

This harrowing scenario of alienation and lost love is thankfully punctured

by bouts of earthy humour. The acting is so electric the cast almost sits in

your lap.

The Times: Killing the cat

August 31st, 1990

Date: 08/31/1990

Author: Harry Eyres

David Spencer has written a play about the noxious effects of child abuse,

which is notable for the absence of campaigning rhetoric and accusing fingers,

and in which the social services are never mentioned. Perhaps it would be more

accurate to say that he is concerned with the breakdown of proper channels of

communication, which includes love, within a family – a breakdown which

incestuous love freezes and enforces rather than resolves. The effect in this

fine production directed by Sue Dunderdale has something of the dark intensity

of O’Neill (no accident that this is a family of Irish origin, living in West

Yorkshire) and also his structural awkwardness.

In Shimon Castiel’s design, the Theatre Upstairs stage is arranged

lengthways, giving it an uncommon breadth, to form a dingy, basement-like space

full not only of bicycles, dustbins, television and cat food but also of the

impediments of the past. This allows the play to develop simultaneously at

different levels of time.

Two of these are defined by the ages of the two actors playing Danny, the son

of the family who (in the present) has come back up north as an unemployed

writer to confront his and his family’s past. This Danny is taken with raw

energy, anger and desperation by Sean Bean. He also appears as a boy of 14,

played with quiet sensitivity by Dominic Kinnaird. Danny is the conscience and

recording angel of the family; the fact that he has written a book called

Killing the Cat, which reveals the family’s dark secrets, enables other

characters reading from it to speak what they would not normally say.

At the centre of the action is Danny’s father Sam, an immigrant Irish factory

worker imbued with charm, dignity and rich vowels by Henry Stamper. Behind the

charm lies an orphanage upbringing, violence, and a feeling that drink excuses

most things but not the stealthy abuse of his daughter Shelagh; he drinks to

erase the guilt.

Spencer is stronger on his male characters than on the female ones who are

the obvious victims. The sisters Kathy (Kate McLoughlin) and Shelagh (Sally

Rogers) react much more stoically than Danny, accepting that life must continue,

though the bricked-up room seems more and more like a prison. Their mother Joan

(Valerie Lilley) is seen at one point in catatonic despair, then walks out

without comment.

Listener: Killing the cat

August 9th, 1990

Date: 09/08/1990

Author: Matt Wolf

What increasingly seems to be the Royal Court’s house style – short, sharp

plays written in jagged, non-naturalistic stabs – is reinvigorated in David

Spencer’s “Killing the Cat” (Theatre Upstairs), the Soho Theatre Company

offering that won this year’s Verity Bargate award. Spencer lives in Berlin,

but his play returns him to the terrain of his earlier works, “Releevo” and

“Space”: working class Yorkshire and families living in a crisis that they can

barely articulate. His authorial alter ego, a writer named Danny (Sean Bean),

makes his need to comprehend itself a theme of the play, as the various

incidents from his turbulent childhood and adolescence are interlaced with

excerpts from the book, Killing the Cat, which we see him offering up to sister

Shelagh (Sally Rogers) for approval.

“Maybe I’ll write a comedy,” Danny tells his boozing father Sam (Henry

Stamper) at the end, in a curtain line that nicely avoids any possible

melodrama. And yet the mordant sarcasm of the remark is inescapable in the

light of what the play unfolds – a life marked by cycles of violence, pain and

repression, in which the sins of the swaggering Irish father seem inevitably to

be visited on his brooding and introspective Yorkshire son.

Uniting all the characters is a need for “the way out”, as Danny’s other

sister, Kathy (Kate McLoughlin), puts it. While Danny finds a catharsis of

sorts in prose, Sam seeks his escape route in drink, shutting out the memory of

prior incestuous episodes with Shelagh which Danny, discovering these belatedly,

calls on him to confront. Relegated to the sidelines is Danny’s divorcee

mother, Joan (Valerie Lilley), a woman condemned by her own inarticulacy to want

from life one thing which she couldn’t name, “so she couldn’t ask for it.”

Sufficiently expressive is the ashen-faced, wide-eyed Lilley that the part seems

even more disappointingly underwritten.

Sue Dunderdale’s direction makes adroit use of every aspect of the small

Court studio, as the six actors (Danny is in fact shown as two selves, Bean’s

questing adult and Dominic Kinnaird’s troubled child) lay bare a shared history

of unvoiced wishes and vague hopes, some of which, Spencer implies, may yet be

answered. On a hot night punctuated by thunder showers outside, this exemplary

company generated that unusually electric heat which comes from witnessing a

relatively unknown playwright on the verge of a breakthrough.

FANTA BABIES

August 1st, 1990

Royal National Theater Studio Encounters Project.

Sprachen:

- Englisch

- Deutsch

FANTA BABIES

August 1st, 1990

Royal National Theater Studio Encounters Project.

Languages:

- English

- German

Royal National Theater Studio Production.

RELEEVO (June 1987)

Soho Poly Theater

Soho Poly production

Dublin Theater Festival Sept. 1987

Birmingham School of Speech and Drama Sept. 1995

Whats’s On: Killing the cat

May 9th, 1990

Date: Dale Arden

Date: Dale Arden

Author: 09/05/1990

“Killing the Cat” opens with a fragmented sequence of moments from a family’s

history, past and present. Although the links between the fragments at first

seem obscure, each moment has perfect emotional clarity. The effect is

kaleidoscopic, as little shards of atmosphere, each one razor sharp at the

edges, gradually begin to resolve themselves into a pattern.

In a decaying house that was once the family home, Danny prowls around

sniffing out the past like a bloodhound. If the past won’t deliver itself into

his hands, he’ll hunt it down.

Danny’s mother used to tell him “You’re alright son.” but that was before she

went through the psychiatric mill, before they “plugged her into the national

grid system”. She wasn’t mad, she was just “fatigued with sadness”. Danny’s

sister Shelagh once thought that the things her father made her do were

“alright”, because if it’s your Dad and he tells you it’s alright, it must be.

Lost in an endless loop of actions, reactions and repetitions, Danny can’t

see a way of getting clear of any of it. “I’m not alright and I tell you I’m

not alright.” Sociologically speaking everyone in “Killing the Cat” is a victim

of some kind; but it’s not a play about passivity and victimisation, it’s about

loving, being sad and getting on with it. The characters are dynamic, if

confused, participants in their own lives.

The play received the 1990 Verity Bargate Award, and quite right too. David

Spencer’s writing is poetic, on the ball and very much alive. He manages to

play out a thread of real humour in the grimmest situations while avoiding the

pit of saccharin that lurks around the “make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry” school of

drama. This production by the Soho Theatre company is beautifully directed (by

Sue Dunderdale) and the cast of six are universally excellent. Highly

recommended.

Posts

Posts Posts

Posts